Listening is key to learning and the entire body is involved in listening.

The most common struggle dyslexics experience is an inability to read. They have extreme difficulty identifying letters, converting those letters into sounds and putting them together to make words.

During the times of the apprenticeship era, there was not the great need to read as there is today. People learned by observing and doing. Kinesthetic learning was the norm.

With the dawn of the industrial revolution, however, there arose the need to educate the masses to work in the resulting businesses.

The invention of the printing press merged perfectly with this need for mass education. This made it possible to put knowledge into a system that could be spread out on a national level. Hence, the proliferation of textbooks. Only then did those with dyslexic minds begin to have problems.

According to Dean Bragonier, founder and executive dyslexic of NoticeAbility, the dyslexic mind is able to “look at a situation, identify seemingly disparate pieces of information and blend those into a narrative or tapestry that makes sense” to them. Most people are unable to perceive the situation in the same way.

This ability translates into levels of exceptional success needed in some vocational paths, for example, entrepreneurship, engineering, architecture and the arts.

In spite of that, they are at a great disadvantage during their years in school.

There are three ways of accessing information: eye reading (print books), ear reading (recorded or audiobooks), and finger reading (braille). While information is commonly made available in braille for blind children, dyslexic children are mandated to eye read print books, and when they have trouble doing so, are labeled as lazy, stupid or unmotivated to learn.

Ear reading is not new. As early as 1931, the American Foundation for the Blind and the Library of Congress Book for the Blind Project established the Talking Book Program. Here is an abridged history of audiobooks:

1934: The first recordings are made for the Talking Book Program and include parts of The Bible, The Declaration of Independence, and Shakespeare’s plays.

1948: The Recording for the Blind program is founded (in 1995 renamed Recording for the Blind and Dyslexic, and in 2011 renamed Learning Ally).

1952: Caedmon Records is formed in New York and is a pioneer in the audiobook industry.

1955: Listening Library is founded and is the first to distribute audiobooks to libraries and schools.

1970s: Libraries start carrying audiobooks.

1985: Publishers Weekly identifies 21 audiobook publishers including Caedmon, Recorded Books, Books on Tape, Harper and Row, and Random House.

1980s: Bookstores start to display audiobooks on bookshelves instead of in separate displays.

1986: The Audio Publishers Association is created.

1997: Audible debuts the first digital audio player.

2011: Audiobook self-publishing becomes possible with the Audiobook Creation Exchange (ACX).

2012: Audiobook annual publication increases 125% from 7,200 to 16,309.

(Source: The Audio Publishers Association)

Dyslexic clinical psychologist, Dr Michael Ryan, gives some recommendations when using audiobooks:

With this longstanding history, I wonder why aren’t schools more accepting of ear reading as a method for testing the knowledge of those children who are dyslexic, and audiobooks for textbooks?

What has been your experience with audiobooks?

Have you used recorded textbooks for your children?

Parents usually assume that their children are seeing normally. That’s not always the case.

According to the American Optometric Association, up to 80% of a child’s learning in school is through vision! This makes you child’s visual health extremely important.

Did you know that 1 in 10 children has a vision problem that’s significant enough to impact their learning? In the United States, that translates to over 5 million children.

Three vision skills necessary for optimal learning are:

Visual Acuity

When you take your child to the pediatrician, he gets a typical vision screening. Have you ever wondered if those screenings are foolproof? The National Center for Biotechnology Information says that at least 50% of vision problems are missed by typical screenings.

In addition to that, being assured that your child has 20/20 vision only tells you he can see at a distance. It does not dismiss the possibility of visual focusing, coordinating or tracking problems – all related to learning.

Convergence

Both eyes must work together, effortlessly and without hurting. That’s convergence. When they don’t quite work together, most likely, the child will sees words on a page bounce around. The child may then tell you that the words are blurry or swimming.

Most children under seven years will assume that everyone sees like they do and say nothing.

When this eye-jumping happens in a classroom, the child may complain of feeling tired, headaches (across the forehead, above the eye brows), and/or aching eyes. Some children tilt over to one side to read, thus creating a way to read with only one eye. For these children, reading is linked with distress and comprehension of what is read is low.

Convergence problems can also cause writing problems, because of poor hand-eye coordination.

Visuospatial Attention

Skilled readers are able to focus on individual words within a cluttered page of text, and after a word has been identified, they must rapidly shift their gaze to fixate on the next word in the line. These changes in visuospatial attention must occur rapidly and accurately to enable fluent reading of a page of text.

When the eyes do not move smoothly along together, the child skips words and phrases, or entire lines while reading.

A 2007 study showed that dyslexics have visuospatial attention deficits that parallel their deficits in some linguistic measures, like verbal short-term memory.

Does your child

It may be dyslexia, or it may be learning-related vision problems.

Be observant!

If you suspect your child is having vision problems, contact the College of Optometrists in Vision Development to locate a developmental optometrist in your area.

Have you ever had to take your child for vision testing because of learning difficulties?

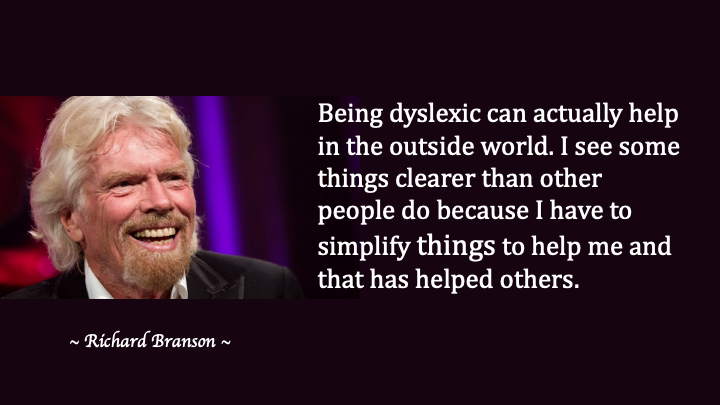

“I was dyslexic, I had no understanding of schoolwork whatsoever. I certainly would have failed IQ tests.” ~ Richard Branson

Sir Richard Charles Nicholas Branson was born on July 18, 1950, at Blackheath, London. His father was a barrister and his mother a flight attendant. His academic performance was poor. He was always interested in becoming an entrepreneur, so he dropped out of school at age 15, to start his first business…a magazine named Student. Listen to this interview in which he credits dyslexia with helping him.

He founded the Virgin Group in the 1970s. In 1984, he started Virgin Atlantic Airlines. In 2004, he founded spaceflight corporation Virgin Galactic, based at Mojave Air and Space Port, for the SpaceShipTwo suborbital spaceplane designed for space tourism. Today, his group controls more than 400 companies in various fields.

Having faced a lifetime of failures, Branson noted, “I suppose the secret to bouncing back is not only to be unafraid of failures but to use them as motivational and learning tools.”

Branson learned he was dyslexic as an adult. In one of his many interviews, he counseled, “Never give up… Fight, fight, fight to survive.”

Talking about dreams, he says, “If your dreams don’t scare you, they are too small.”

Do you have a dream that scares you?

Have you asked your children (dyslexic and non-dyslexic) about their dream lately?